Category: Learning from Home

Design Your Own 18th-Century Kite

Duration: 20-30 minutes

Recommended Ages: Everyone ages 5-8 with some supervision and anyone age 9 or older with minimal to no supervision.

Description: Unleash your creativity in this arts and crafts activity as you cut out and decorate an 18th-century kite. What will your kite have? Suns, moons, and stars are popular.

Colonial Games

Kites were flown by many people in the 18th century, though they were used most frequently by wealthy men and boys. You might even have heard of the most famous kite-flyer of the 18th century: Benjamin Franklin! He left us with a description of his simple kite. It was a square of silk fabric tied onto a wooden frame. Other kite shapes existed in the colonial period. No matter the shape, some were plain, and some had lots of decorations.

Art such as paintings, drawings, and woodcuts give us a lot of information about 18th century-kites. Plus, a few kites used more than 200 years ago have survived. Some colonial kites looked the way you might imagine; they were diamond-shaped. However, the shape that appears most often is a “pear.” People gave this style of kite its name s because they thought it looked like an upside down pear. Primary sources show that most of the time all styles had lots of shapes and letters drawn, sewn, or glued onto them. Stars, moons, and suns were popular. Initials also decorated many 18th-century kites. Perhaps the initials were for the kite’s owner. Another way to decorate was to attach inward facing triangles along the edge.

Follow the directions below to print an outline of a kite. Then decorate it in whatever way you would like. Will you make your kite look like those from the colonial time? Or will you design a more modern kite? If you want to make a different kind of kite, you can use the printout to make an outline and glue tissue paper to make a translucent, decorated kite to hang in your window.

Design Your Own 18th-Century Kite

What you need

Kite Print out

Coloring materials such as a pencil, colored pencils, crayons, markers, pens

Construction paper (optional)

Glue (optional)

1. Print out your choice of the diamond- or pear-shaped printout, and decorate it to your heart’s content.

2. If you wish, you may also download the stars, moon, and sun printout to glue to your kite.

Making Rosemary Stem Cuttings

Duration: 30-45 minutes to set up (plus 1-2 minutes daily for 30-60 days)

Recommended Ages: Suitable for ages 7-11 with minimal adult assistance and age 12 and older without supervision.

Description: Garden at home by growing rosemary from stem cuttings, and learn how cuttings were important in the 18th century. Over the next few months, your cuttings will develop roots and become new plantlets.

Colonial Gardening

While we often think of starting new plants from seeds, we should not overlook propagating—or making new plants—from cuttings of existing specimens. The process of taking stem cuttings is especially useful when you need to be certain of what you are growing. Some plants are unpredictable when they start as seeds. For example, an apple grown from seed may be sour, mealy, tart, sweet, or bitter, no matter what was the taste of the original apple. In these situations, using seeds is a bit like rolling a handful of dice! Gardeners almost always reproduce apples, peaches, pears, and other fruits from cuttings. Like identical twins, a plant grown by cutting is genetically the same as the mother plant.

Fruit trees were among the first crops planted by English settlers in the new world. Colonial planters understood the best way to reproduce fruit trees, and they often used cuttings. Almost two centuries after the first Europeans arrived in Jamestown, Virginians were still using this technique.

George Mason wrote in 1787 to his son John requesting “a few young Trees of the best kinds of Pears and Plums, by any Ship to Potomack River. . .also a few young Grape Vines, of good kinds; the roots should be carefully covered with Moss, or some such thing, or set in Boxes of Earth.” Colonists preferred cuttings, or small trees grown from cuttings, for two reasons. Cuttings helped colonists be sure that the variety they received was desirable. Only the most wealthy colonists could afford to purchase trees–rather than small cuttings–shipped across the ocean.

Cuttings were also used over shorter distances. George Washington recorded in his diary in April of 1785, “[Colonel] Mason. . . sent me some young shoots of the Persian Jessamine & Guilder Rose.” This type of exchange was common in this time period. George Mason and others sought rare plants because they enjoyed gardening, used their gardens to display their status, and hoped to improve the resources available to American farmers.

Discover the basics of growing plants from cuttings and build your 18th century skills! Making new plants from cuttings is exciting.

What do you need

Plant Materials: Look around for what is available. For example, can you find some live rosemary, lavender, sage, or fig. Fresh rosemary cuttings sold at grocery stores may also be used.

Soil: If possible, open a new bag of potting mix. A bag you have already opened but recently purchased is ok, too. Soil mixes labeled for potting are generally better than topsoil or soil dug in your backyard. Potting mixes better avoid compacting over time and are easier for new roots to work into. If your cuttings rot, it is possible the mix is carrying soil borne diseases. Clean the vessel with soap and water. The 1 to 2 cups of soil used for cutting propagation can be microwaved for 90 seconds in a microwave safe container, allowed to cool, and then returned to the vessel.

Small Pot or Container: Your cuttings will be 4 to 6 inches. Their containers may be small. A small pot 3 or 4 inches deep, a 6 oz mason jar, or a coffee cup is about the size you are looking for. If you use something without a hole or two in the bottom, add some rocks or broken crockery to create a small drainage pace–still, be extra mindful about over-watering. You may put 2 to 3 cuttings in one pot.

Scissors or knife

Water

Spray Bottle: This item is optional.

Auxin or Rooting Aid: This is an optional ingredient. This method gets good results without plant hormones, but the powders are effective in speeding up rooting.

Paper and Pencil: For notes, sketches, and questions

1. Prepare your container by loosely filling it with soil and moistening the dirt with water. If your soil is really dry, you may find it helpful to pour some of it in a bowl, add water, and mix it with your hands. It is easy to make the mistake of just wetting the surface while the bottom stays totally dry–this will kill your cutting!

2. Find a healthy rosemary plant, or another plant from that materials list above. If you want to experiment with another plant, that is fine, too. If you do not have access to a plant ask around. Rosemary commonly overwinters in Virginia. Perhaps a neighbor can pass a piece of a healthy plant over the fence. If you are not under a stay-at-home order, check with friends or family. They may have rosemary or other plants to try, and they might be happy to exchange a few cuttings for some new plants in a month or two.

3. Use scissors to cut 4 to 6 inch long cuttings. Your cuttings should include some of the brown woody part of the stem and some new growth at the opposite end (top of the cutting). The woody part will look light brown and appear bark-like.

4. Next you will remove all the leaves from the bottom half of the cutting. Plants breathe through their leaves. As they breathe, water moves from the roots and out of the plant in a process called transpiration. If too much water leaves, then the cutting will dry out and die. By removing leaves we are slowing the plant’s water loss.

5. Using your scissors or a knife gently scrape the top layer of bark from the bottom inch of your cutting. This ‘wound’ helps the plant grow roots more quickly by helping it jump start its healing process. This wound and healing process works in a way that is similar to the way exercise helps us get stronger. The exercise ‘wounds’ our muscles making us feel sore or tired, but as we recover we become stronger than before. Cuttings build new roots, stems, and leaves as they recover.

6. Slide your prepared cutting into your container. Make sure the “wound” is underneath soil. Dirt that is to 3 inches will usually work well for this type of cutting. Place your container where you will see it everyday that is warm and receives some sun.

7. Take notes. Include the date. Make columns, so you can record when you watered your cuttings.

8. Check your container daily. Make sure the soil remains moist at all levels. You can check with a toothpick and visually. Insert a toothpick. It should feel wet when you pull it out. Wet soil will also appear darker. Overtime, it will become easy to tell if the cuttings need water. If it is too dry your cutting will not root. If you notice lots of algae it is too wet. Imagine the soil is a slightly wet sponge, from which you can squeeze only a few drops of water. A spray bottle may be helpful at this step.

9. Once a week gently tug on your cuttings. If they come up easily take a look. You may see root nodes or tiny roots. Either way, return them to the soil. If they do not come out easily, they may have started growing tiny roots. Write in your notes the date you saw roots. If you could no longer pull your cutting up, record that. Include how many cuttings formed roots.

10. Your cuttings should have substantial roots after several months. At this point you may plant them outside or in a larger pot. Be careful about introducing them to the sun too quickly. A few days outside in partial sun will help them adapt to more light and warmer temperatures. Plants can sunburn just like we can!

Questions:

Imagine you were George Mason’s son John, and you just discovered a new kind of plant. As you examined the plant, you thought maybe you could make 2 or 3 good cuttings without harming the plant. Next, you decided to send pieces of it to several leading citizens, so they could help you make more of the rare plant.

- How might you pack it to make sure it had enough water and air?

- Who would you send your cuttings to?

- Pick an important figure from the colonial period. Write a letter to that person describing where you found the plant, how the plant looked, and how you think people might use it.

The Founders as Gardeners

Many of our founders, like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, and James Madison, were Virginia landowners who sold crops from their huge estates. By selling cash crops from these plantations and by not paying most of their workers, these leaders and their families achieved immense wealth. They believed agriculture would be important in building our country’s future. They thought that they could help.

Each of these founders felt that as a leader of Virginia (and later, the United States), it was their responsibility to share agricultural resources with other people. These resources often included new seeds or cuttings. New crops had the potential not only to provide food for American families, but also to yield surplus products for sale in American and European markets. Men such as George Mason thought that successful farmers would be the type of citizens the United States needed to build a thriving democracy.

Elite Virginian landowners had the time and resources to think about experiments, propagation, and sharing seeds and cuttings largely because of work provided by enslaved, indentured, and paid servants. Less wealthy people had less leisure time for such activities. Many Virginians needed to spend most of their time on the backbreaking work of everyday life.

Advanced propagation from cuttings—grafting!

Many people in the 18th century were familiar with propagation by cuttings, but fewer people had the more advanced skills needed for grafting. When grafting, an horticulturist takes a cutting and merges it with another growing plant in order to combine the good traits of both plants. Fruit trees are often grafted. The top, or scion, is usually a tasty variety, and the bottom is a hardy root, often called the rootstock.

Grafting was common during the colonial period. For example, George Washington recorded in 1765 a substantial list of grafts, “Grafted 48 Pears. . .12 Spanish Pears. Next to these are 8 Early June Pears then 10 latter Burgamy—then 8 Black Pear of Worcester—and lastly 10 Early Burgamy. Note all these Pears came from Colo. Masons.” George Mason’s immense orchard planted by his tenant farmer Thomas Halbert likely utilized cutting propagation and grafting. The indenture contract (today we would call it a lease) from 1752 required, “an Orchard of two hundred Winter Apple Trees, at thirty feet Distance every Way from each other, and eight hundred Peach Trees, at fifteen Feet Distance every Way from each other. . .well trimmed, pruned, fenced in, and secured from Horses, Cattle, and other Creatures.” Colonists had many uses for fruit. They could eat it fresh, dry it to eat in winter and early spring, and use it to make alcoholic beverages. As a result, they needed a lot of fruit trees. The high-level skills needed to make cuttings, graft, set-up and care for orchards and gardens were in high demand in eighteenth century Virginia.

Many elite Virginian hired or indentured servants to manage their elaborate kitchen gardens and orchards. This skilled work gave gardeners and orchardists higher status than some other laborers and allowed some of them to receive better living quarters, rations, pay, or even land at the end of contract. George Mason’s choice to use Thomas Halbert to set up an orchard was not unusual. We know George Washington hired or indentured five different gardeners at Mount Vernon.

For paid servants and indentured servants, gardening provided a chance for upward mobility that was unavailable to the enslaved people working along side those indentured or paid servants. Gardening skills were portable, and free people who possessed them were likely to find it relatively easy to get work. Working in a garden could offer some opportunity for enslaved people. People in bondage who gained gardening skills may have been able to use those abilities to supplement their own diets by creating kitchen gardens in the yards next to their dwellings.

Gardening from Your Pantry

Duration: 20-30 minutes for set up plus 30-45 minutes for gardening math, 1-2 minutes daily for +10-14 days for checking on the seeds

Recommended Ages: 5-8 with heavy adult assistance, 9-12 with minimal adult assistance, and 13+ and older without supervision.

Description: Prepare to garden by testing seeds in your pantry and last year’s seeds. When you finish, plan and plant your garden using probability to estimate how many seeds you will need.

Colonial Gardening

Everyone in the 18th century had a connection to agriculture. Depending on the colony, between 75 and 90% of the population worked at farming or some closely related enterprise. Even In towns and cities, most people had at least small kitchen gardens. As a result, seeds were important to everyone. Seeds presented choices: they could be grown into new plants and eventually more seeds, shared among neighbors, fed to livestock, ground into meal, used as food, or sold to other colonies or England.

While everyone interacted with seeds, not everyone understood seeds in the same way. Poor and enslaved individuals valued the seeds they owned as the difference between food security and starvation. Wealthy Virginians like George Mason were deeply interested in agriculture. But they did not do the actual planting, weeding, and harvesting themselves. Instead, they had others plant and tend their crops.

During this time, people defined gentlemen as those men who were so wealthy that they did not need to work with their hands as blacksmiths, silversmiths, shoemakers, other artisans, and laborers did. Gentlemen could spend their time on intellectual activities, including scientific experimentation. George Mason’s interest in collecting, growing, and experimenting with rare seeds was an appropriate hobby for a gentleman, and it symbolized his wealth and elite status. Gardening for pleasure was one pastime George Mason shared with George Washington. The two men sent many kinds of seeds, tree starts, and plants to each other. One time, Mason passed along watermelon seeds to his friend and neighbor.

Most Americans today do not grow their own food, but just about everyone has seeds hiding in their kitchens and pantries. By performing a seed test similar to what farmers have done for centuries, you can find out if your seeds are good only to eat or if they can use them to start or expand your garden.

Conducting a Seed Test

What do you need

Assorted Seeds: See Step 1.

Plate: Find a plate with a little lip. A few square plastic containers will also work well.

Paper Towels

Water

Paper and Pencil: For notes, sketches, and questions.

Directions:

1. Find seeds. Do you have any old seed packets? If so, they are perfect to test. Many seeds grow well even several years old! Check your pantry. Do you have dry beans like black, kidney, chickpeas, or lentils? Or, whole spices like coriander, cumin, dill or fennel? (The ground versions won’t work.)

Do you have any dried peppers with seeds inside? Be careful handling them! The pepper seeds may have oils that can cause your skin or eyes to burn. You might want to wear gloves when working with pepper seeds.

Grains like rice, barley, popcorn, or quinoa might grow in this test and be fun for experiments. However, because they take up a lot of space, are more difficult to grow, and produce less food per square foot than some other plants, they might not be a cost effective plant to grow in a kitchen garden.

2. Place a few sheets of paper towel on your plate. Pour enough water to moisten the towel. Don’t add too much! If you add too much water your seeds will not be able to breath, and they will slide everywhere. A plastic baggy or tupperware may also work for this step–just make sure the plastic does not create an airtight seal! Remember the seeds are alive and need air!

3. Place around 10 seeds of each type together on the paper towel. Note on your piece of paper or in a notebook the day’s date and list the seeds you selected going in a circle. Make sure you know where your circle starts!

Questions:

Which seeds do you think will germinate, and why?

Why is too much water bad for seeds?

What factors or qualities might stop a seed from growing?

4. Check daily. Add water as needed. The seeds must stay moist. Remove any seeds that show signs of rot and record them as seeds that did not grow. Take notes and/or sketch what you see.

Do you like art?

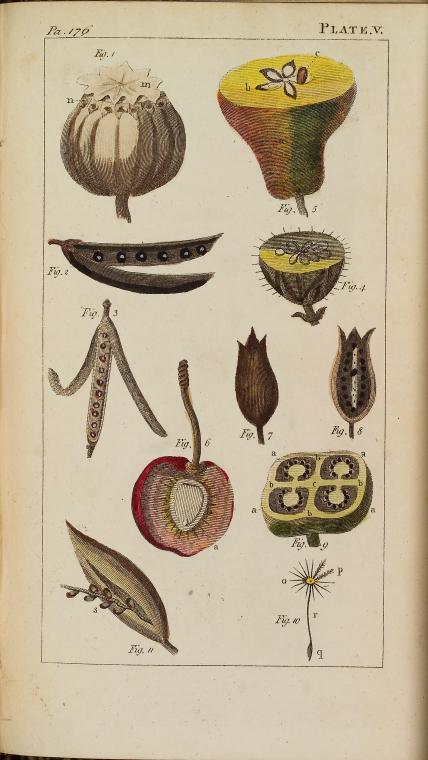

Go one step further. Draw and label the different seed parts: seed coats, primary root or radical, seed leaves or cotyledon, and the true leaves. You can use the 18th-century image above as inspiration.

5. Most seeds should show some signs of germination within the first week. A few may show signs within a few days!

6. After 10 to 14 days, declare your test done.

7. Count the number of germinated seeds and compare it to the total. Give each seed a fraction or a percentage. This number is called percent germination.

Questions:

Create a list starting with the highest percent germination and ending with the lowest.

Which seeds had the highest value?

Which seeds had the lowest?

How did the test results match your predictions?

How might you improve your seed test?

Go plant! Consult your chart to decide which seeds will be the most likely to succeed in your garden. If you had any types of seeds that grew well, then they could be good choices for your garden. If most of your seeds grew, use them as normal. If only a few of them sprouted, consider planting extra seeds in a small area. If you are wondering about how best to plant a specific seed and do not have a seed pack to refer to, then consider visiting a seed company’s website. These companies provide great information on how deep to plant seeds and how far apart to space them.

Seeds: Who was doing what ?

Gentlemen of the highest social classes, like George Mason, managed their fields and gardens, but they did not work their land. They had other people, some free but many held in bondage, perform nearly all of the garden and field work. The free time wealthy men enjoyed allowed them to think about seeds as symbols for our new nation or as products to be sold. Slave owners used some seeds, such as corn, to provide rations for the people they kept in slavery.

Average farmers, tenant farmers, or poorer families understood seeds in more practical terms than gentlemen farmers did. Almost all people with farms used some seeds to grow cash crops or sent some for grinding into flour or cornmeal. But, for many people, seeds mostly provided food for their families, fodder for their animals, and seeds for future years’ plantings. Enslaved peoples likely had even more reasons to closely manage their seed supply. Saved seeds offered the promise of food the next year. People with the fewest resources were usually the most careful to preserve what little they had. If they did not care for their seeds, families and communities went hungry or struggled to survive.

Learn how to use your seed test data to calculate garden plantings.

Calculating Seed Germination

Farmers have to make choices based on the limited information they have available. This has always been difficult because weather, bugs, and even seeds may not work as predicted. The solution is not as easy as planting more seeds because planting too many seeds could be just as bad as planting too few. Some crops do not grow correctly if planted too closely together or they may be more vulnerable to diseases or pests. Farmers sometimes plant a little more seed just to be safe, and after the crops have come up, they remove plants to get the spacing right. This work is time consuming. Math has always been helpful in managing the risks of having too few and too many plants.

This example explains how to use percent germination to decide how many seeds to plant. Percent germination tells you the probability a seed will germinate. Imagine, a seed test showed that 8 out of 10 kale seeds grew. You created the fraction 8/10, the percentage 80%, and the decimal .80 to predict how many plants might grow if you planted different numbers of seeds. To estimate the value of seeds that would grow from a given number of seeds you multiply the number of seeds by the fraction, percent, or decimal. The result is the number of seeds you expect to grow. The table below shows the equation and total plants for 20, 30, or even 50 seeds. Remember, 8/10, 80%, and .80 are all the same!

(Number of Seeds Planted) X (Fraction or Percent Germination) = (Total Plants)

| 10 | 8/10 | 8 |

| 20 | 80% | 16 |

| 30 | .80 | 24 |

| 50 | 8/10 | 40 |

1. Could you reverse this process? If you wanted to grow 36, 40, or 50 plants how many seeds would you need?

(Number of Seeds Planted) X (Fraction or Percent Germination) = (Total Plants)

| 8/10 | 36 | |

| 80% | 40 | |

| .80 | 50 |

First, ask if you expect the number of seeds to be larger or smaller than 36.

Now, set it up in our equation:

(Number of Seeds Planted) X (Fraction or Percent Germination) = (Total Plants) (Number of Seeds Planted) X .80 = 36

2. Now divide both sides by .80 to get 45. You would need about 45 seeds to grow 36 plants. Can you find the number of seeds planted if 40 or 50 plants grew?

3. Because you know 80% is an estimate, you may want to plant more in the garden. You will have to use your judgement. 50 or 55 might be a good number.

4. Now imagine you had 3 feet of space in your garden. You know you should have a kale plant every 9 inches. You also know that your seed germinates 80% of the time. It is okay if you have to pull out a few plants from each spot, but not too many. You need to make sure there will be a plant at each spot. Drawing a diagram may help! Remember there are 12 inches in 1 foot.

- How many plants or plant spots will you have in 3 feet?

- How many seeds will you plant at each spot?

- Do you think you will have more than one plant in each spot?

Practice! If you conducted a seed test use the percent germination values you created. Otherwise, use our example values. Use measurements from your garden, or pretend you have a 12 foot long garden space.

The table below shows the results from our seed test.

| Seed Type | Seeds that grew | Total Seeds |

| Chickpea | 12 | 13 |

| Pinto Bean | 8 | 11 |

| Black Lentil | 4 | 10 |

| Pepper | 3 | 7 |

| Cilantro | 1 | 10 |

Using each of your different seeds, how many plants would likely grow if you planted 25, 35, or 60 seeds?

Could you reverse this process? If you wanted to grow 15, 24, or 50 plants how many seeds would you need?

How many seeds would you plant if you knew your seed had 67% germination, that you needed a plant every 6 inches and you had 6 feet of space?

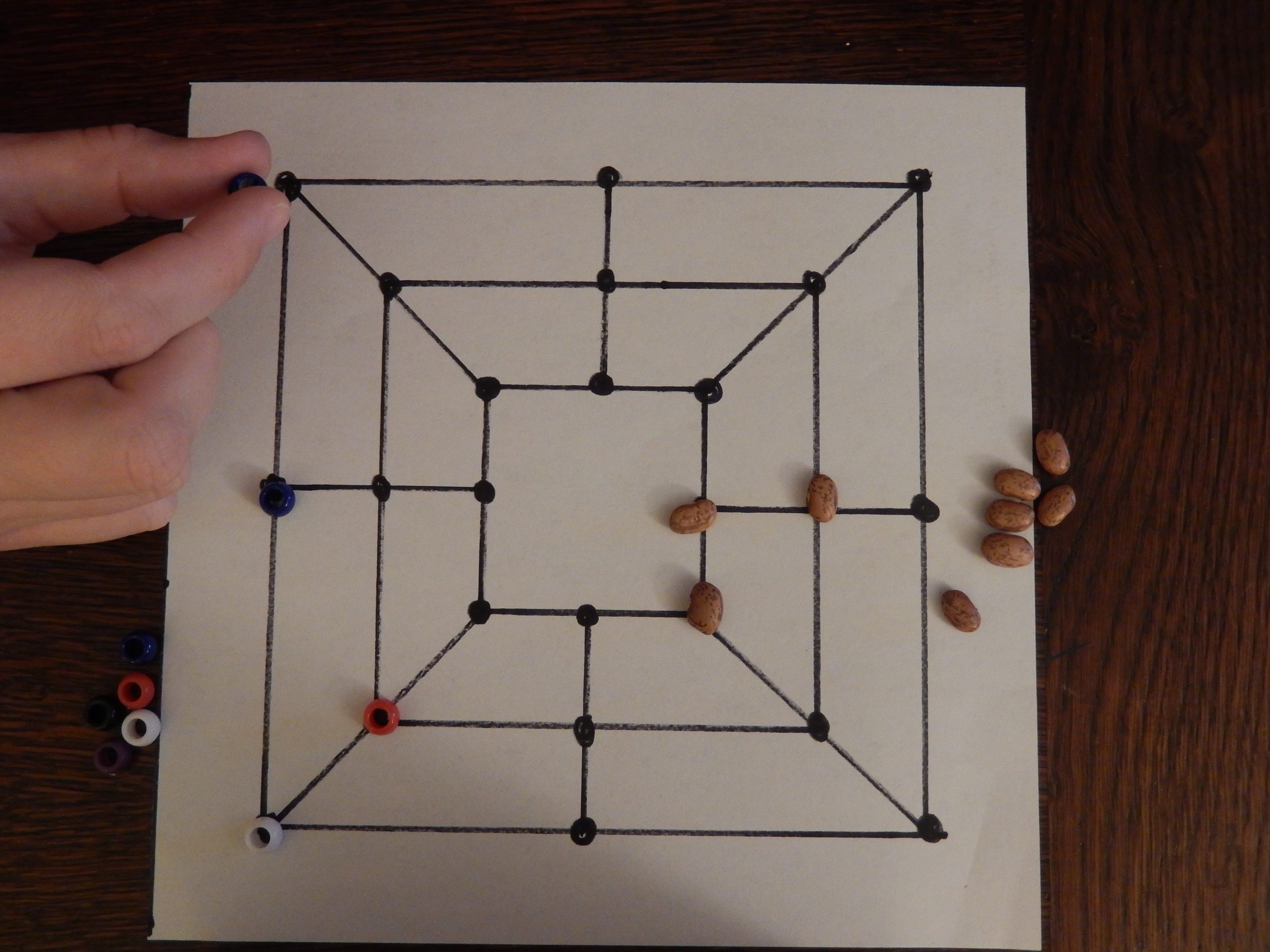

Make a Nine Men’s Morris Board

Duration: 10 minutes for making the board, 10-15 minutes for playing the game

Recommended Ages: Suitable for anyone ages 9 and older

Description: Make and play a game that was popular with Revolutionary War soldiers.

Colonial Games

Most people in the 18th century worked or went to school six days a week. They usually had only Sunday for leisure time. While they had less free time than we have, people of all ages still found time for fun.

Soldiers fighting in the American Revolution, especially, had a lot of responsibilities. But even they found time for games. With no vehicles to transport their belongings, common soldiers had only what they could carry in their own packs. Some of them found room for a pack of cards, but most did not have room for other gaming materials.

How did soldiers manage to play games, if they could not carry equipment with them? They had to be creative. Board games such as Nine Men’s Morris required very few supplies. All soldiers really needed were two distinct sets of game pieces, such as rocks, acorns, or pieces of twig. They might have used a stick to scratch a game board in the dirt. Because it was so easy to improvise the game’s equipment, people could play Nine Men’s Morris anywhere.

At first glance, Nine Men’s Morris is similar to tic-tac-toe. It is a two-person game, and the goal is to take turns to place, and eventually move, your markers into a line of three. In this game, three-in-a-row is called a mill.

But unlike in tic-tac-toe, once you have moved your “men” into your first mill, you are not done. When you get three-in-a-row, you get to capture and remove one of your opponent’s markers from the game. Be careful! Your opponent will look for opportunities to create mills and therefore remove your pieces. The game ends when one player has only two markers left, or no more moves can be made.

For detailed instructions on playing the game, including how to make your own board, keep reading.

Make a Nine Men’s Morris Board and Play the Game

What you need

A surface to draw on Be creative! You might make a board you can reuse out of paper or cardboard. Or you might make a temporary board on a driveway or sidewalk You could even mark on dirt.

Writing materials such as a pencil, colored pencils, crayons, markers, pens, sidewalk chalk, or a stick

Scissors (if using paper)

Ruler (if using paper)

2 sets of 9 game pieces (or “men”) such as buttons, beans, rocks, legos, shells, paperclips, or other materials you have at home. Just make sure that you can tell the difference between the set for each set player.

1. First we need to make a square of any size. It is hard to play if your square is too small, though. Use your ruler to determine how long the short side of your piece of paper is. For example on copy paper, the short side is 8.5”. This size square works well.

2. If you want to make your board on a piece of copy paper, use your ruler to measure out 8.5” along the long side of your paper, and draw a line there. Cut the paper all the way along that line.

3. Draw three squares on the paper, one inside the other so that they get smaller in the center of the board.

4. Draw a circle or dot at the corner of each of the squares, and in the center of each line making up the square.

5. Draw lines connecting the dots on the center of the lines. Congrats, you’ve finished your board! It’s time to find someone to play with.

6. You decide who goes first. Take turns. Each turn, one player places one man on a dot. No two pieces may share a dot; each man must have its own dot.

7. Your goal is to try to get three in a row. If you are lucky enough to make a row of three, you get to capture one of your opponent’s pieces. Take it off of the board and put it in a little pile next to your own men.

8. Once you and your opponent have finished taking turns to put all men on the board, you will begin the next part of the game. Take turns sliding your markers one space at a time to make new lines of three in a row. You may move your markers only one space at a time, and they must move along one of the lines on the board. You may not jump other markers or to another part of the board! You may slide from one dot to another if the two dots are connected by a line, and the place where you are going does not have another man on it.

9. Just as in the first part of the game, every time you get three in a row (a mill), you get to take one of your opponent’s markers. Add it to your pile of captured pieces.

10. Keep going until one of you can no longer make a mill, either because you have only two men left or because you are completely blocked from moving.

Do you want to make your board more challenging? Remove the diagonal lines to look like the one below. Both designs are historically accurate.

Standards of Learning: Classroom and At Home Activities

Activity |

Virginia Standards of Learning |

C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards |

| Battledore: Turn arts-and-crafts into a chance to learn about schools in the 18th century by making a battledore! | K.1; 1.1; 2.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by:

K.3 The student will sequence events in the past and present and begin to recognize that things change over time. |

D2.His.2.K-2. Compare life in the past to life today.

D2.His.4.K-2. Compare perspectives of people in the past to those of people in the present. |

| Design Your Own 18th Century Kite: What will your kite have? Suns, moons, and stars are popular. | K.1; 1.1; 2.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by:

|

D2.His.2.K-2.Compare life in the past to life today.

D2.His.9.K-2. Identify different kinds of historical sources. |

| Kite: Make a kite, and play like children in the 18th century. | K.1; 1.1; 2.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by:

|

D2.His.2.K-2. Compare life in the past to life today.

D2.His.9.K-2. Identify different kinds of historical sources. D2.His.10.K-2. Explain how historical sources can be used to study the past. |

| Kush: Taste a dish that has roots in Africa and makes use of ingredients available to people who were enslaved. | K.1; 1.1; 2.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by:

|

D2.His.2.K-2. Compare life in the past to life today. |

| Nine Men’s Morris: Make and play a game that was popular with Revolutionary War soldiers | K.1; 1.1; 2.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by:

K.3 The student will sequence events in the past and present and begin to recognize that things change over time. |

D2.His.2.K-2. Compare life in the past to life today.

D2.His.4.K-2. Compare perspectives of people in the past to those of people in the present. |

| Sweet Potatoes Broiled: Make and taste a dish influenced by Native American peoples. | K.1; 1.1; 2.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by:

|

D2.His.2.K-2. Compare life in the past to life today.

D2.His.9.K-2. Identify different kinds of historical sources. |

| Sweet Potato Slips: Prepare your garden for the summer and fall by learning how to propagate sweet potatoes, as well as the importance of sweet potatoes the 18th century diet.

|

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

|

| Whirligig: Find out about an archaeological discovery and use it to make your own toy. | K.1; 1.1; 2.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by:

K.3 The student will sequence events in the past and present and begin to recognize that things change over time. |

D2.His.2.K-2. Compare life in the past to life today. |

Activity |

Virginia Standards of Learning |

C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards |

| Battledore: Turn arts-and-crafts into a chance to learn about schools in the 18th century by making a battledore! | VS.1, USI.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

USI.5 The student will apply social science skills to understand the factors that shaped colonial America by

|

D2.His.2.3-5. Compare life in specific historical time periods to life today.

D2.His.4.3-5. Explain why individuals and groups during the same historical period differed in their perspectives |

| Colonial Seed Culture: Test seeds for your garden | Social Sciences

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

Science Life Processes 4.4 The student will investigate and understand basic plant anatomy and life processes. Key concepts include

Scientific Investigation, Reasoning, and Logic 6.1 The student will demonstrate an understanding of scientific reasoning, logic, and the nature of science by planning and conducting investigations in which

|

| Colonial Seed Germination Calculations: Calculate the ratios and percentages of seed germination. | Mathematics

Probability and Statistics 4.13 The student will a)determine the likelihood of an outcome of a simple event;

Measurement and Geometry 5.8 The student will

Probability and Statistics 5.15 The student will determine the probability of an outcome by constructing a sample space or using the Fundamental (Basic) Counting Principle. 6.2 The student will

Computation and Estimation 6.5 The student will

Patterns, Functions, and Algebra 6.13 The student will solve one-step linear equations in one variable, including practical problems that require the solution of a one-step linear equation in one variable. 6.14 The student will

|

| Design Your Own 18th-Century Kite: What will your kite have? Suns, moons, and stars are popular. | VS.1; USI.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

|

D2.His.2.3-5. Compare life in specific historical time periods to life today

D2.His.9.3-5. Summarize how different kinds of historical sources are used to explain events in the past. |

| Keeping a Diary: Explore the importance of diaries as primary sources. | VS.1, USI.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

|

D2.His.6.3-5. Describe how people’s perspectives shaped the historical sources they created.

D2.His.9.3-5. Summarize how different kinds of historical sources are used to explain events in the past. D2.His.13.3-5. Use information about a historical source, including the maker, date, place of origin, intended audience, and purpose to judge the extent to which the source is useful for studying a particular topic. |

| Kite:Make a kite, and play like children in the 18th century. | VS.1; USI.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

|

D2.His.2.3-5. Compare life in specific historical time periods to life today

D2.His.9.3-5. Summarize how different kinds of historical sources are used to explain events in the past. |

| Kush: Taste a dish that has roots in Africa and makes use of ingredients available to people who were enslaved. | VS.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

USI.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

USI.5 The student will apply social science skills to understand the factors that shaped colonial America by

|

D2.His.2.3-5. Compare life in specific historical time periods to life today |

| Nine Men’s Morris: Make and play a game that was popular with Revolutionary War soldiers | VS.1, USI.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

USI.5 The student will apply social science skills to understand the factors that shaped colonial America by

|

D2.His.2.3-5. Compare life in specific historical time periods to life today.

D2.His.4.3-5. Explain why individuals and groups during the same historical period differed in their perspectives |

| Rosemary Stem Cuttings | Social Sciences

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

Science Life Processes 4.4 The student will investigate and understand basic plant anatomy and life processes. Key concepts include

|

| Sweet Potatoes Broiled: Make and taste a dish influenced by Native American peoples. | VS.1; USI.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

VS.3 The student will demonstrate an understanding of the first permanent English settlement in America by

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

USI.4 The student will apply social science skills to understand European exploration in North America and West Africa by

USI.5 The student will apply social science skills to understand the factors that shaped colonial America by

|

D2.His.2.3-5. Compare life in specific historical time periods to life today |

| Whirligig: Find out about an archaeological discovery and use it to make your own toy. | VS.1, USI.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

VS.4 The student will demonstrate an understanding of life in the Virginia colony by

USI.5 The student will apply social science skills to understand the factors that shaped colonial America by

|

D2.His.2.3-5.Compare life in specific historical time periods to life today. |

Activity |

Virginia Standards of Learning |

C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards |

| Keeping a Diary: Explore the importance of diaries as primary sources. | D2.His.6.6-8. Analyze how people’s perspectives influenced what information is available in the historical sources they created.

D2.His.10.6-8. Detect possible limitations in the historical record based on evidence collected from different kinds of historical sources.

|

Activity |

Virginia Standards of Learning |

C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards |

| Keeping a Diary: Explore the importance of diaries as primary sources. | D2.His.6.9-12. Analyze the ways in which the perspectives of those writing history shaped the history that they produced.

D2.His.8.9-12. Analyze how current interpretations of the past are limited by the extent to which available historical sources represent perspectives of people at the time |

Keeping a Diary

Duration: Minimum 10 minutes daily

Recommended Ages: Anyone who can write without supervision.

Description: Diaries can help both the writer and later historians to understand the events of a particular time. Prompts in this activity will help you figure out what to write and guide you to think about how diaries can be used as historical sources.

Primary Sources: Diaries

On April 18, 1769, George Mason went to the home of his neighbor George Washington. Together, the men spent the next two days riding the boundary of their land, completing surveying work. After they agreed on the exact edge of their properties, George Mason sold some of his land to George Washington In the afternoon Mason returned home to Gunston Hall.

How do we know what Mason and Washington were doing on those four days? Because Washington kept a diary.

People write journals and diaries for many reasons. Sometimes it is because of extraordinary events in the world. Some people find writing every day or two helps them organize their thoughts and memories. George Washington kept a diary most of his life. He included details about unusual life events like his trip to Barbados and his time fighting in the French and Indian War. He also wrote about the day-to-day activities on his plantation. John Adams was another consistent diarist. Adams started his diary when he was a boy. He mixed descriptions of his daily life with many other kinds of information. Adams used his diary to keep track of his expenses. Sometimes he copied down favorite poems.

Famous individuals are not the only ones who keep diaries. Philip Vickers Fithian was a tutor who kept a diary while working at a Virginia plantation in 1773-74. He wrote about the differences in daily life in Virginia versus his home in New Jersey. Elizabeth Drinker recorded so many details of her life in Philadelphia that throughout her life, she filled 36 blank books.

All diaries are important to historians. The diaries of Washington, Adams, Fithian, and Drinker help us better understand life in the 18th century.

Since many of George Mason’s peers kept diaries, it is likely he did, too. Unfortunately, over time, lots of historical documents get lost. No one has ever found Mason’s diary.

Today, many people who have never kept a diary are trying it out. Many new diarists think that it will be important to remember what life was like during the coronavirus pandemic. These documents will help the people who write them remember this time. And, they may become important primary sources for historians of the future.

You too can write a diary or journal about your experiences.

Activity: Starting your Journal or Diary

What you need:

Pen or pencil

Notebook, bound journal, or lined paper

Or

Computer or voice recorder

There is no wrong or right way to keep a diary. If you need help, try these prompts or hints.

1. If you’re having trouble getting started, try introducing who you are, where you live, what your family is like, or something similar.

2. Describe your day. How has your routine changed? What would you be doing normally, and why aren’t you?

3. Are there things that you miss? Are there things that you like more? Why?

4. Did something funny happen today?

5. Provide as much detail as you want. Washington’s diary entries are sometimes very short, while Adams frequently wrote several paragraphs describing everything he did. Don’t stress about including every detail however. It is impossible to write down every little thing that happened or affected your day.

After you’ve written your diary or journal entry, think about the following:

6. What were some of the details you included, and why were they important to you?

7. What were some of the details you did not write down? Does it matter that you did not include them?

8. Imagine you are a historian in the future using your journal or diary as a primary source. What questions might that historian have about your life?

More about using diaries and journals as sources

Diaries and journals are some of the most important sources historians have for learning about colonial life.. These documents give us details about everyday activities and feelings that do not usually appear in other kinds of sources such as letters, newspapers, paintings, official documents, and objects from the past.

Not everyone was able to keep a diary. Paper was very expensive, and many people did not have enough for a diary. Plus, many people who lived during the colonial period could not write. Even some people who knew how to read never learned how to form letters themselves. In Virginia, most white men knew how to write their names, and about half of white women could do the same. We do not know how many white people could read. Historians estimate that fewer than 10 percent of people who were enslaved could read or write. A few more free black Virginians had those skills.

Because most diaries that have survived from the colonial period are from wealthy people, we know more details about their lives than we do the lives of other people.

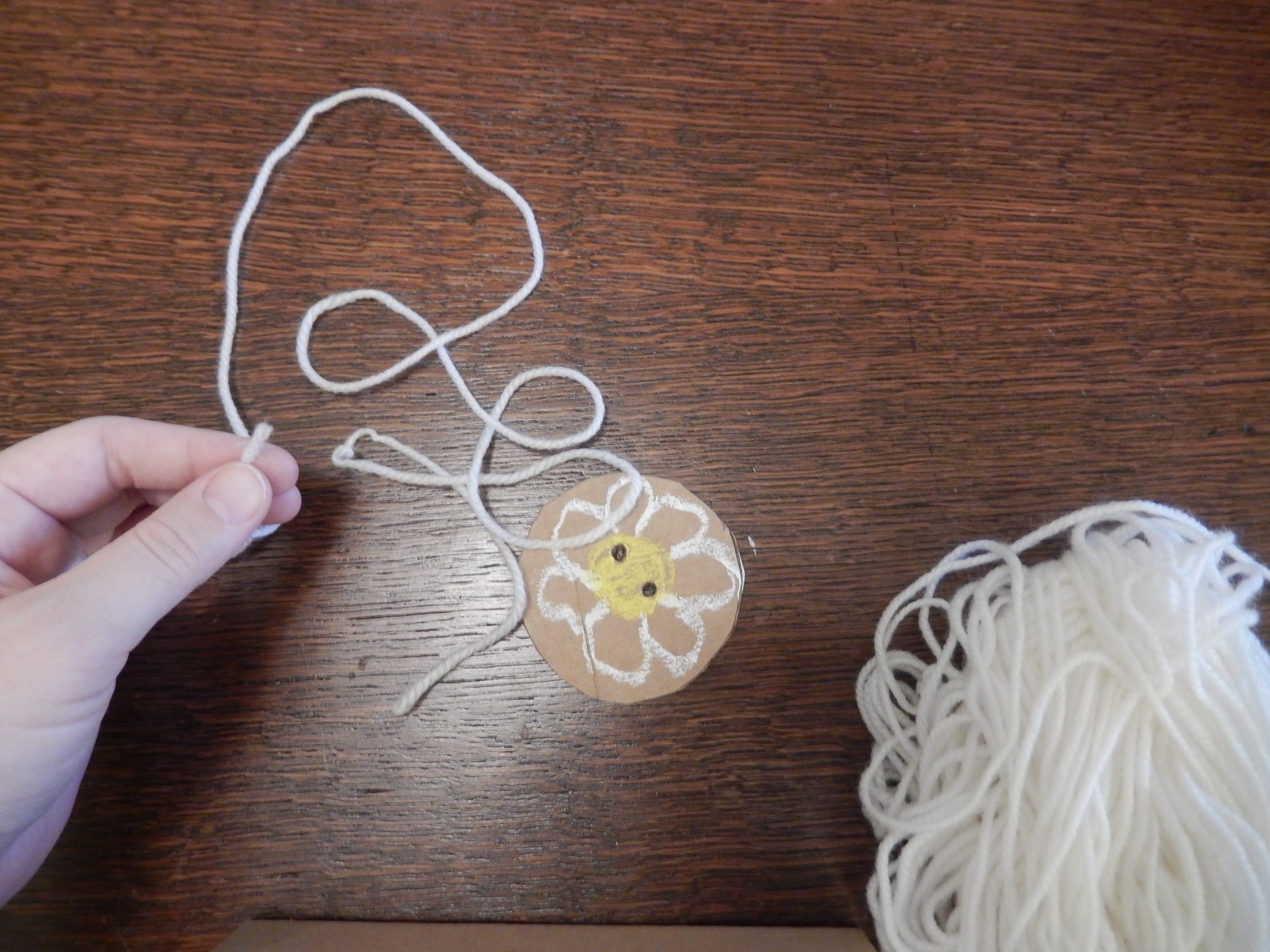

Make a Whirligig

Duration: 10-30 minutes for making the game, as long as you like for playing the game!

Recommended Ages: 5-12 with adult supervision, 13+ with minimal to no adult supervision

Description: Find out about an archaeological discovery and use it to make your own toy

Colonial Games

People of all ages played with games and toys in the 18th century. Often these amusements were homemade. Can you think of a hand made toy you’ve played with? Maybe a friend or family member made something special for you. Or perhaps you invented your own game. You might have used your imagination to turn a stick into a sword or a wooden spoon into a magician’s or fairy’s wand.

Paintings, letters, diaries, and other sources tell us about card games, board games, dolls, and other toys. We do not know much about what toys existed at Gunston Hall. Adults probably played with cards and enjoyed some board games. Children in the Mason family, including Nancy, John, and Betsy, may have read books, played with puzzles, and had other toys. Children who were enslaved, including Vicky, Bob, and Peter, may have found special treasures in the forest, and they may have invented games for themselves. They might have even made toys for themselves.

Courtesy of The Virtual Curation Lab

From our archaeological digging, we know that at least one person at Gunston Hall played with a whirligig. Our archaeology team discovered a half of a flat circle of metal. Two holes are in the middle. Maybe someone made the whirligig from a coin or from a scrap piece of metal.

A whirligig—or buzzsaw— is a disk threaded onto a loop of string and twirled around. Twirling the string creates a twist. Once it is twisted enough, the string tightens on your fingers and makes them come towards each other. Then you can pull them out again. The goal is to have a smooth back and forth motion. When whirligigs spin, they make a whirring sound that gives the toy its name.

Today you can make a whirligig with objects you have in your house.

Activity: Make a Whirligig

Method 1:

What you need

Large button with 2 or 4 holes (buttons with shanks will not work)

String or yarn

Scissors

1. Measure your string using the length of one arm. Pinch the end of the string in your fingers and pull the length up to your shoulder. If you’d like to use a ruler, measure 32 inches.

2. Thread your string through the holes in your button, creating a loop with your circle in the middle. (If you’re using a 4-hole button, use only 2 of the holes.) Tie the ends of your string in a knot.

3. Put the two end loops of the string over your index fingers and move the button to the middle of the string. Hold out your arms and flip the string, in a circle. You should be spinning your fingers away from yourself. Do this until the string is very tight.

4. Tug your hands apart gently. The string will begin to unwind, and the whirligig will start to buzz. As the tension slackens, slowly bring your hands back together, and the whirligig will spin itself back up.

After you practice for a while, you should be able to keep the whirligig going for a long time!

Method 2:

What you need

Heavy cardboard like the flap of a box

Coloring materials such as a pencil, colored pencils, crayons, markers, pens

Construction paper (optional)

Glue (optional)

String this can be yarn, kitchen twine, or whatever string you have in the house

Scissors

1. Use the bottom of a glass or soda can to trace a circle onto your cardboard, and cut it out with scissors.

2. Mark two holes in the center, about 1/2-inch apart (that’s about the width of your thumb or forefinger). Carefully punch them out with your scissors, a knife, or a pen.

3. Now it’s time to decorate! Color to your heart’s content or cut shapes from your construction paper and glue them to your circle.

4. Measure your string using the length of one arm. Pinch the end of the string in your fingers and pull the length up to your shoulder. If you’d like to use a ruler, measure 32 inches.

5. Thread your string through the holes in your button, creating a loop with your circle in the middle. Tie the ends of your string in a knot.

6. Put the two end loops of the string over your index fingers and move the button to the middle of the string. Hold out your arms and flip the string, in a circle. You should be spinning your fingers away from yourself. Do this until the string is very tight.

7. Tug your hands gently apart. The string will begin to unwind, and the whirligig to buzz. As the tension slackens, slowly bring your hands back together and the whirligig will spin itself back up.

After you practice for a while, you should be able to keep the whirligig going for a long time!

What else could you use to make a whirligig? Sometimes people take a slice of a tree branch and drill two holes in it. Other people punch holes in circles of metal. You might even try a thick disk of leather.

Make Your Own Battledore

Duration: 5-30 minutes

Recommended Ages: 5-8 with some adult assistance, 9-12 with minimal adult supervision

Description: Turn arts-and-crafts into a chance to learn about schools in the 18th century by making a battledore!

Colonial Learning

When Betsy, Nancy, John, Thomson, and the other Mason children were young, Virginia and the other colonies did not have a system of public schools like we have today.

Everyone learned skills. Some people learned how to tend chickens, grow crops, make clothes, or be a blacksmith. Only some children had the opportunity to learn how to read and write.

At Gunston Hall, the Mason children had a schoolhouse all to themselves. Their parents hired teachers for them. One teacher was a man named Mr. McPherson. He lived in a little room upstairs in the schoolhouse. He taught the children subjects such as reading, writing, math, science, and geography.

As they got older, the boys spent time with their father learning how to do his work. The boys also went away to live at small private schools. The older girls learned skills from their mother and from another teacher called Mrs. Newman.

Colonial children who were able to attend school did not have many special books or supplies for school. One learning tool many used was called a battledore. You can make your own by following the directions below.

Activity: Make your own battledore

What You Need:

Use what you have on hand

Paper such as light-colored construction paper, copy paper, card stock, or thin cardboard. Cut it to 5 x 11 inches.

Writing materials such as a pencil, colored pencils, crayons, markers, pens

Scissors

Ruler

1. Read all the instructions before you do anything.

2. Turn the paper sideways, so it is in landscape orientation. Cut 3½ inches at the top, so you have a long rectangle that is 11 inches long and 5 inches high.

3. Use your ruler to fold over an inch of the left hand side of the paper. Then fold the rest of the paper in thirds. See the drawing to the left for more information.

4. Now you have six big sections, or pages, plus the little section on the left hand side.

5. Start filling the pages of your battledore. Battledores helped children learn the alphabet.

- Use your best handwriting to print the alphabet. Can you write it in cursive, also?

- Add some proverbs, wise sayings, or a prayer.

- Make a grid of boxes. Write a letter of the alphabet in the corner and draw a picture in the box of something that starts with that letter.

6. Think about what else to put in your battledore. Here are some ideas from colonial examples:

- Write out all the vowels.

- Make a row of numbers from 1 to 10. Add more, if you would like.

- Include a list of words that you think are good for beginning readers. Do you want them to rhyme? Or should they all start with the same letter?

7. Decide on a title. Turn your battledore sideways, and write your title and the date on the outside of the little section.

Do you want to make your battledore look more like one from the colonial period? In the 1700s, many people thought the letter “i” was the same as the letter “j” and that “u” was the same as “v.” To make your battledore look colonial, don’t include “j” and “u” in your alphabet.

Show how much you know about life during the colonial period by drawing only objects that existed during that time. What will you need to leave out? There were not any cars, televisions, or computers! What else should be missing?

More about learning in the colonial period

In colonial Virginia, the more money a family had, the better chance a child had to learn to read and write. Very wealthy families hired teachers just for their own children. Sometimes families with lots of money sent their children to live with teachers. These students attended tiny schools instructors had in their homes.

Kids who did not attend school learned from their parents. If they were apprentices, they might have some lessons from the master craftsman. Some people during the colonial period learned how to read but not how to write. Historians estimate that most white men at least knew how to sign their names. About half of white women seem to have been able to write their names. During the colonial period, it was not against the law to teach people who were enslaved in Virginia to read and write. Still, historians believe that fewer than ten percent of enslaved Virginians knew how to read and write.

Not everyone could afford printed learning materials. They might have a slate they could use to practice writing by copying what someone else wrote or what they saw in a book or newspaper.

Some Virginians who were really poor, including some people who were enslaved, practiced writing by using a stick to mark in the dirt.

Kush

Duration: 5 minutes for prep, 20 minutes for cooking

Recommended Ages: 5-12 with adult supervision, 13+ with minimal to no adult supervision

Serving Size: ¾ cup

Description: Taste a dish that has roots in Africa and makes use of ingredients available to people who were enslaved.

Uncovering the foods of people who were enslaved in colonial America requires some detective work. On every historical topic, people of the past wrote down less than we would like. And, as enslaved women and men had little access to writing and printing materials, they passed down most of their recipes by word of mouth.

Recipes for kush appear around time of the Civil War. But there’s evidence that the food is much older. In fact, 18th-century West Africans likely brought a form of the word “kush” with them when they were kidnapped from their homeland. In Senegambia kusha was a grain-based dish. It was the ancestor of the dish enslaved people made with new world ingredients. Today, many people eat a modern form of Kush when they prepare cornbread dressing at Thanksgiving.

In the past, kush made use of ingredients that were available in just about every slave household. With the addition of onions, pot liquor, and some spices, kush transformed leftover cornbread into an amazing, and flavorful, dish for the table.

This video is provided through the generosity of Townsends. Check out their historic cooking series on YouTube and their website: townsends.us.

Our recipe is adapted from one shared with us by culinary historian Michael Twitty, when he visited Gunston Hall in 2017. More information about this recipe and historic African foodways can be found on his site: afroculinara.com.

Adaptation

1 batch cornbread, preferably day-old

1 onion, chopped

1 tbsp butter, oil, or lard

1-2 cups pot liquor or your preference of stock

Salt, crushed red pepper to taste

- Crumble your cornbread into a bowl and set aside.

- Heat your skillet over medium-high heat, and add the butter. Once the butter has melted, add chopped onion to the pan, and saute until softened.

- Add in spices to taste and mix well.

- Add in your reserved cornbread, and a small amount of the liquid. Stir frequently, until the mixture is heated through. Add more liquid as necessary, until the mixture thickens.

- Taste and add additional spice as desired.

- Serve hot.